The Trial

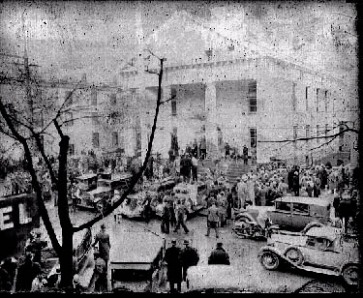

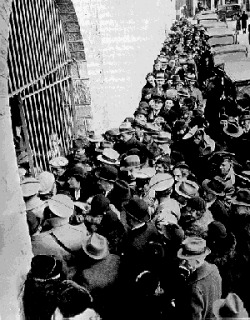

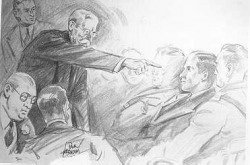

The trial, which the renowned acerbic journalist and critic H.L. Mencken called "the greatest story since the Resurrection," took place in the county seat, Flemington, New Jersey. It was indeed a circus, with hundreds of reporters and spectators swelling the small town to several times its population.

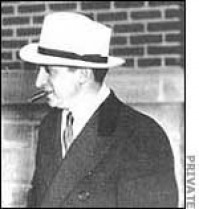

The prosecution was led by the Attorney General of the State of New Jersey, David T. Wilentz, thirty-eight years old. Wilentz and his prosecution team completely outmatched Hauptmann's lawyers. Wilentz, who was trying his first criminal case as attorney general, was a dapper, cigar-smoking, confident little man who built a convincing circumstantial case. He is almost always photographed with a broad grin, a cigar, sometimes with a white fedora with a brim turned down in the manner of a New York dandy or the gangster Al Capone. Despite his smiling charm, his eleven hours of cross-examination of Hauptmann was quite savage, and his summation emotional, dramatic, and impressive.

The New York Journal offered to provide Hauptmann with a well-known Brooklyn defense attorney, Edward J. Reilly. He was assisted by a local Flemington attorney, well respected but inexperienced in criminal defense, C. Lloyd Fisher.

It is tempting to attribute much of the responsibility for Hauptmann's conviction to Reilly. Even those works that present the case for Hauptmann's guilt describe Reilly and his courtroom performance in unflattering terms. He was florid, hulking, bombastic —he wore a swallow-tail coat and striped trousers —and something of a boozer. The lunch breaks during the trial often presented Reilly with opportunities to consume a number of drinks. The difference between his morning performances in court, and the afternoons, where he was listless, were noted.

There is little doubt that he invented and hired witnesses, fabricated statements to the press, and deliberately misled the jury. His incompetence even dismayed Hauptmann, who, during the long trial, had only one fifteen-minute private conference with his principal attorney. He alienated his own client, his co-counsels, the jury, and the spectators by his senseless bullying of prosecution witnesses. He missed a crucial opportunity to raise reasonable doubt when, to the complete mystification of his colleague, Lloyd Fisher, he conceded that the corpse of the child discovered by William Allen was indeed Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. Much of his cross-examination was an attack on the competence of the police officers and their investigation.

Although paid $25,000 by the New York Journal for his work, he later sent Mrs. Hauptmann a bill for an additional $25,000, attempting to get his cut of the action from her fund-raising efforts to support her husband's appeals.

Two weeks after the verdict, drunkenly raving, he was taken away to a Brooklyn hospital in a straightjacket. A few weeks after that, he was back in action, but disinclined to sue the Hauptmanns for additional legal fees.

by Russell Aiuto